Mastering the Foundation of the Internet: IPv4 What Is It and How Does It Work?

NETWORKINGROUTERSIPV4IP ADDRESSES

Welcome to the foundational layer of computer networking! If you’ve ever wondered how your phone loads a website or how a simple email finds its way across the globe, the answer lies in a short string of numbers: the Internet Protocol (IP) address.

The IP address is arguably the single most important concept in all of networking. It is the virtual identifier that allows every device, from a massive corporate server to the tiny sensor in your smart toaster, to be uniquely located and communicate with everything else online.

This comprehensive guide will take you from the very basics of what an IP address is, through the deep mechanics of the most common version, IPv4, and teach you the essential skill of understanding its binary language, which is the key to unlocking the power of subnetting.

1. Defining the IP Address: Location and Identity

At its core, an IP address serves two fundamental purposes, often compared to the address system of the physical world:

Identification: It names a specific network interface.

Location: It provides the information necessary to locate that interface in the network topology and route data to it.

Think of an IP address as a Street Address for a device. Just as a physical address guides a letter to your house, the IP address guides a digital packet of data to your specific computer or server.

Without a unique address, data would have no idea where it came from or where it was going, rendering the entire internet unusable.

IP vs. MAC Address: A Crucial Distinction

While the IP address provides the logical, routable address (the street address), there is another crucial address involved: the MAC (Media Access Control) address.

A router uses the IP address to decide which path (network) to send the data packet down, but the final switch or host uses the MAC address to deliver the packet to the correct device on the local network segment. They work together to make sure the data gets to the intended destination.

2. Introducing IPv4: The First Version Of the Internet Protocol (IP)

The current workhorse of the internet, though increasingly supplemented by IPv6, is Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4). It was developed in the 1980s and is responsible for routing most of the traffic you see today.

The IPv4 Anatomy: 32 Bits, Four Octets

An IPv4 address is a 32-bit number. These 32 bits are logically grouped into four sections called Octets, with each octet containing 8 bits. This adds up to the 32 total bits. 8 4 = 32

Octet: A group of 8 bits. "Octet" comes from the Latin root octo, meaning eight. There are four octets in every IPv4 address.

Bit: The smallest unit of data, representing either a 0 (off/false) or a 1 (on/true). There are 8 bits per octet or 32 bits total in every IPv4 address.

Since 2^8 = 256, the decimal value of any single octet can range from 0 (all 8 bits are 0s) to 255 (all 8 bits are 1s). Which, will make more sense when we discuss binary, later on.

Dotted Decimal Notation (DDN)

The reason we see IPv4 addresses as 192.168.1.1 is because we use Dotted Decimal Notation (DDN). This is the human-readable format where the decimal value of each of the four 8-bit octets is separated by a dot.

If we took the address 192.168.1.1 and wrote it in the language the computer understands (binary notation), it would look like this: 11000000.10101000.00000001.00000001

These 1s and 0s are the bits we were talking about earlier. All 1s in any octet will equal 255 and all 0s in any octet will equal 0.

Now this gives us A LOT of unique IP addresses. 4,294,967,296, or about 4.3 billion unique IPv4 combinations. You can find this using the formula 2^32 (2 to the 32nd power), since there are 32 bits, and binary numbers (Base 2) rely on powers of 2 for their place values.

While this seems like a massive number, with the explosion of the internet and IoT devices, we ran out of IPv4 addresses, leading us to create some work arounds (and why IPv6 was developed).

But, before we discuss this lets look back at all those bits (the 1s and 0s). What are they telling us and how does 192.168.1.1 mean the same thing as: 11000000.10101000.00000001.00000001

Let's take a look at what is happening here between binary and IPv4 addresses.

3. The Language of Computers: Binary Conversion

To master IP addressing, you must be able to convert addresses between Dotted Decimal Notation (DDN) and Binary. This is the key to understanding subnetting and the subnet mask.

The Power of Place Value: Base 2

Binary numbers (Base 2) rely on powers of 2 for their place values. In any 8-bit octet, each position has a specific decimal value, starting from the rightmost bit (2^0) and moving to the leftmost bit (2^7).

Memorize the 8-Bit Place Value Chart!

The total sum of these values is 255. (128 + 64 + 32 + 16 + 8 + 4 + 2 + 1 = 255)

You've probably already noticed but the decimal weight values double the previous one, moving from right to left.

Before we move on take a moment to copy this chart, write it down, or lock it into your memory somehow. This chart is going to be one of your most valuable tools when you're working with IP addresses or subnets.

Method A: Dotted Decimal to Binary Conversion

To convert a number from DDN to Binary, you can use the Subtraction Method, working from the largest value (128) downward.

Example: Convert the decimal number 172 to binary.

I like to look at this is what can we subtract 172 in this case from without it being a negative number? Then continue doing so until you reach 0, skipping the Decimal Weight Values that would cause the number to be negative if you subtracted it.

(Note: \ge means greater than or equal to)

Is 172 \ge 128? Yes. → Bit is 1/ON. (Remaining: 172 - 128 = 44).

Is 44 \ge 64? No. → Bit is 0/OFF. (Remaining: 44).

Is 44 \ge 32? Yes. → Bit is 1/ON. (Remaining: 44 - 32 = 12).

Is 12 \ge 16? No. → Bit is 0/OFF. (Remaining: 12).

Is 12 \ge 8? Yes. → Bit is 1/ON. (Remaining: 12 - 8 = 4).

Is 4 \ge 4? Yes. → Bit is 1/ON. (Remaining: 4 - 4 = 0).

Is 0 \ge 2? No. → Bit is 0/OFF.

Is 0 \ge 1? No. → Bit is 0/OFF.

Result: The binary conversion for 172 is 10101100.

You'll repeat this process for all four octets of an IP address to convert it to binary.

Method B: Binary to Dotted Decimal Conversion

To convert from Binary to DDN, you use the Addition Method. Simply align the binary number to the weights chart and add the weights that correspond to a 1. In other words there are 8 values on our binary chart (from 128 to 1) and there are 8 bits in each of the four octets.

Simply take the 8 bits and align those with the 8 decimal weight values on the chart. Anything that is aligned with a 1 (meaning ON) we will add together.

Example: Convert the binary number 10110101 to decimal.

The total sum of these values is 172. (128 + 32 + 8 + 4 = 172)

The decimal result is 172 just as we looked at using the subtraction method. Both methods work fine so pick the one that makes the most sense to you and memorize it.

4. Understanding Subnetting: The IP Address Divider

A single IP address alone is not enough to define a device's location. You need the Subnet Mask.

The Purpose of the Subnet Mask

The Subnet Mask is a 32-bit number used by devices to logically divide the IP address into two essential parts:

Network ID (The Street): The portion that identifies the specific network segment (or subnet). All devices on the same physical link must share the exact same Network ID.

The network portion will ALWAYS stay the same for every device on that network

The network portion will be all of the continuous binary 1s in a binary subnet mask.

Host ID (The House Number): The portion that identifies the specific device (the host) within that network segment.

The host portion will be UNIQUE for each device on the network.

The host portion will be the 0s in the subnet mask.

When converted to binary, a subnet mask is defined by a continuous string of 1s followed by a continuous string of 0s:

The 1s represent the Network ID.

The 0s represent the Host ID.

Example: The mask 255.255.255.0 has 24 continuous 1s: 11111111.11111111.11111111.00000000

This tells the router that the first three octets define the Network ID, and the last octet is available for host addresses.

Something important here to notice is that the subnet has 24 continuous 1s. This is where the CIDR notation you see comes from at the end of an IP address. For example 192.168.1.1/24.

If you're unfamiliar with CIDR notation we'll discuss that next.

The /24 tells us the subnet mask has 24 continuous 1s going from right to left. If you simply count them you'll end up with 24 as the first 3 octets all contain 8 1s, while the 4th octet contains all 0s.

Now circling back to earlier what does all 1s in binary add up to using our binary weight value chart?

If you said 255 you would be right. (Remember this is 128 + 64 + 32 + 16 + 8 + 4 + 2 + 1 = 255)

Meaning 11111111.11111111.11111111.00000000 is the same as 255.255.255.0

The fourth octet is 0 because all 0s (all bits turned off) in an octet will = zero.

5. From Classes to CIDR: Organizing the Address Space

Before the modern internet, IPv4 was rigidly organized using classes. Today, we use the flexible CIDR (Classless Inter-Domain Router) system.

The Traditional IPv4 Classes

To calculate the number of hosts per network use the formula 2^h - 2 where h is the number of Host Bits (0s) found in that classes subnet mask, such as 255.0.0.0 for class A.

We subtract 2 from each of these because there are 2 addresses that we can't use on a network. This is the first address, which is the Network Address and the last address in the network range, which is the Broadcast Address. So we subtract 2 to find the number of useable hosts on the network.

Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR)

CIDR is the modern standard, developed because the class system was wasteful. A company needing 500 hosts would have to take a full Class B (/16) address block, wasting over 65,000 addresses!

CIDR notation uses a forward slash followed by a number—the prefix length (e.g., 192.168.1.0/26).

The prefix length simply tells you the exact number of Network bits (1s) in the subnet mask.

/24 means the first 24 bits are the Network ID (255.255.255.0).

/26 means the first 26 bits are the Network ID (255.255.255.192).

To find the 192: the 26th bit falls into the 4th octet, giving two network bits (1s) when we line up all 8 bits in the 4th octet with the 8 numbers from our binary weight value chart:

128 + 64 = 192.

11111111.11111111.11111111.(24 bits) 11000000 25th and 26th bits

This flexibility allows network administrators to precisely divide the address space to match their needs, a practice known as Variable Length Subnet Masking (VLSM).

6. Finding the Critical Subnet Addresses

In any given subnet, there are four addresses that you must be able to calculate based on the IP address and the subnet mask.

1. Subnet Address (Network ID)

This is the very first address in the range. It is the address that identifies the subnet itself. All of the Host ID bits are set to 0s. This address cannot be assigned to any host.

2. Broadcast Address

This is the very last address in the range. It is used to send a message simultaneously to all devices within that single subnet. All of the Host ID bits are set to 1s. This address cannot be assigned to any host.

3. First Usable Host Address

This is the first address in the range that can be assigned to a device (like your laptop or a server). It is always the Subnet Address (Network ID) + 1.

4. Last Usable Host Address

This is the last address in the range that can be assigned to a device. It is always the Broadcast Address – 1.

Full Example: Subnet Breakdown

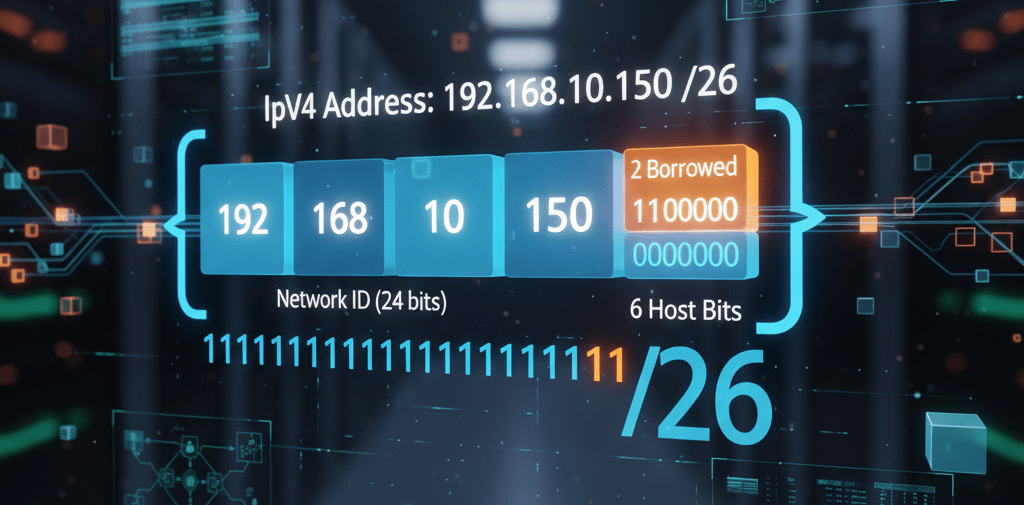

Let’s find all four key addresses for the IP address: 192.168.10.150/26.

Prefix: /26 means the mask is 255.255.255.192.

Host Bits: There are 32 - 26 = 6 host bits. 3.

Block Size (Subnet Increment): 256 - 192 = 64.

We use 256 here because an octet can have 2^8 = 256 possible values, ranging from 0 - 255, and counting 0 as 1 we have 256 possible values.

This means the subnets in the 192.168.10.x range start at: 0, 64, 128, 192, etc.

Identify the Subnet (Network ID): Since 150 falls between 128 and 192:

Subnet Address: 192.168.10.128 (All host bits are 0s).

Identify the Broadcast: The next subnet starts at 192, so the broadcast is the address before it.

Broadcast Address: 192.168.10.(192 - 1) = 192.168.10.191 (All host bits are 1s).

Identify Usable Hosts:

First Usable Host: 128 + 1 = 192.168.10.129.

Last Usable Host: 191 - 1 = 192.168.10.190.

The ability to calculate these addresses confirms your mastery of IPv4 structure.

7. The Future: A Note on IPv6

While IPv4 remains in use, the Internet is steadily transitioning to IPv6 (Internet Protocol version 6) to solve the address exhaustion problem.

Size: IPv6 uses 128-bit addresses (compared to IPv4's 32-bit). This provides a virtually limitless 3.4 \times 10^38 or 2^128 (2 to the 128th power) addresses.

Format: It uses eight groups of four hexadecimal digits, separated by colons (e.g., 2001:0DB8:85A3:0000:0000:8A2E:0370:7334).

For the foreseeable future, networking professionals must understand and manage both IPv4 and IPv6 networks simultaneously.

8. Glossary of Networking Terms

A quick reference for the key terms used in this guide.

Value Delivered Straight To Your Inbox

Save yourself the headache of searching. Subscribe to stay updated with our latest content, industry news, and helpful resources.